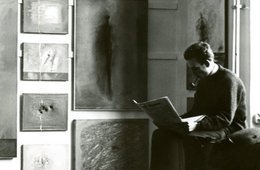

Women (Königin Christine und ihr Stallmeister)

The absence of women in most history painting is striking. If they appear, as in Friedrich Matthäis’ The Murder of Aegisthus (1805/1806), for example, then they do so as secondary figures or victims. An exception is the painting Queen Christine and Her Equerry by Ferdinand von Rayski. Here, the Swedish queen is the main figure. She was been esteemed for her political stance, her interest in science, and also for her role as a woman operating independently in history. However, the painting’s focal point is a history of disappointed love, which relativizes the queen’s historical significance.